×

×

☰

☰

Account abstraction has for a long time been a dream of the Ethereum developer community. Instead of EVM code just being used to implement the logic of applications, it would also be used to implement the verification logic (nonces, signatures…) of individual users’ wallets. This would open the door for creativity in wallet designs that could provide some important features:

It is possible to do all of these things with smart contract wallets today, but the fact that the Ethereum protocol itself requires everything to be packaged in a transaction originating from an ECDSA-secured externally-owned account (EOA) makes this very difficult. Every user operation needs to be wrapped by a transaction from an EOA, adding 21000 gas of overhead. The user needs to either have ETH in a separate EOA to pay for gas, and manage balances in two accounts, or rely on a relay system, which are typically centralized.

EIP 2938 is one path toward fixing this, by introducing some Ethereum protocol changes that allow top-level Ethereum transactions to start from a contract instead of an EOA. The contract itself would have verification and fee payment logic that miners would check for. However, this requires significant protocol changes at a time when protocol developers are focusing heavily on the merge and scalability. In our new proposal (ERC 4337), we provide a way to achieve the same gains without consensus-layer protocol changes.

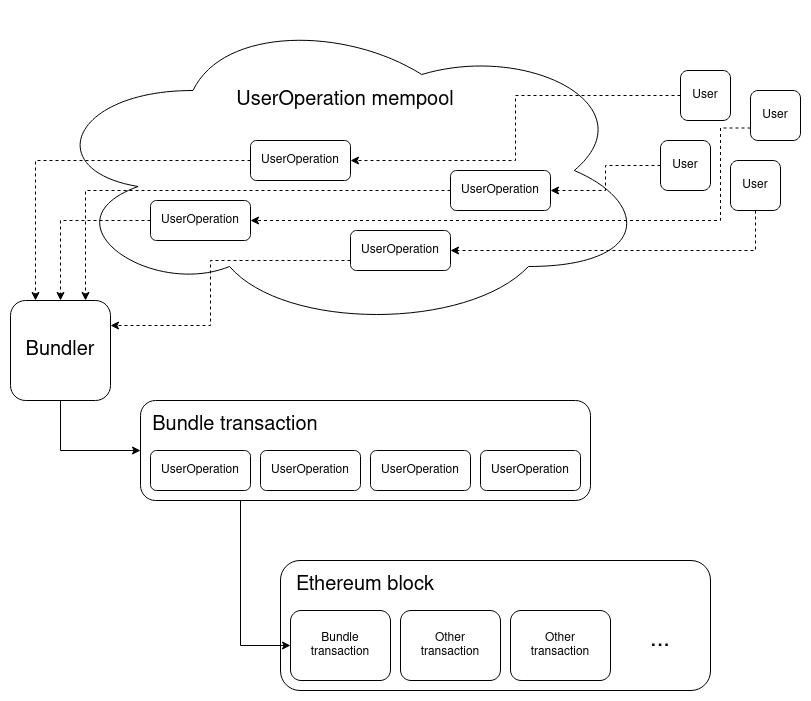

Instead of modifying the logic of the consensus layer itself, we replicate the functionality of the transaction mempool in a higher-level system. Users send UserOperation objects that package up the user’s intent along with signatures and other data for verification. Either miners or bundlers using services such as Flashbots can package up a set of UserOperation objects into a single “bundle transaction”, which then gets included into an Ethereum block.

The bundler pays the fee for the bundle transaction in ETH, and gets compensated though fees paid as part of all the individual UserOperation executions. Bundlers would choose which UserOperation objects to include based on similar fee-prioritization logic to how miners operate in the existing transaction mempool. A UserOperation looks like a transaction; it’s an ABI-encoded struct that includes fields such as:

sender: the wallet making the operationnonce and signature: parameters passed into the wallet’s verification function so the wallet can verify an operationinitCode: the init code to create the wallet with if the wallet does not exist yetcallData: what data to call the wallet with for the actual execution stepThe remaining fields have to do with gas and fee management; a complete list of fields can be found in the ERC 4337 spec.

A wallet is a smart contract, and is required to have two functions:

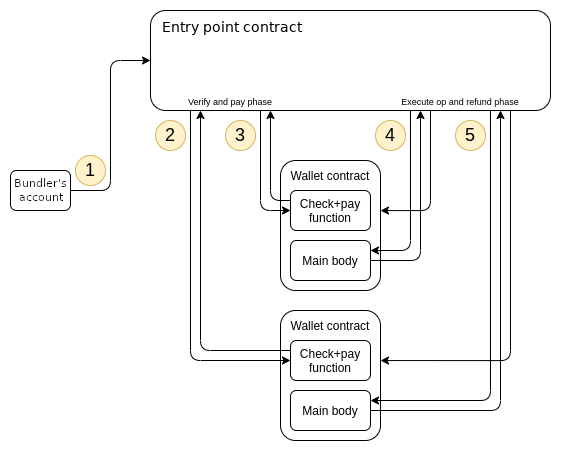

validateUserOp, which takes a UserOperation as input. This function is supposed to verify the signature and nonce on the UserOperation, pay the fee and increment the nonce if verification succeeds, and throw an exception if verification fails.To simplify the wallet’s logic, much of the complicated smart contract trickery needed to ensure safety is done not in the wallet itself, but in a global contract called the entry point. The validateUserOp and execution functions are expected to be gated with require(msg.sender == ENTRY_POINT), so only the trusted entry point can cause a wallet to perform any actions or pay fees. The entry point only makes an arbitrary call to a wallet after validateUserOp with a UserOperation carrying that calldata has already succeeded, so this is sufficient to protect wallets from attacks. The entry point is also responsible for creating a wallet using the provided initCode if the wallet does not exist already.

Entry point control flow when running handleOps

There are some restrictions that mempool nodes and bundlers need to enforce on what validateUserOp can do: particularly, the validateUserOp execution cannot read or write storage of other contracts, it cannot use environment opcodes such as TIMESTAMP, and it cannot call other contracts unless those contracts are provably not capable of self-destructing. This is needed to ensure that a simulated execution of validateUserOp, used by bundlers and UserOperation mempool nodes to verify that a given UserOperation is okay to include or forward, will have the same effect if it is actually included into a future block.

If a UserOperation‘s verification has been simulated successfully, the UserOperation is guaranteed to be includable until the sender account has some other internal state change (because of another UserOperation with the same sender or another contract calling into the sender; in either case, triggering this condition for one account requires spending 7500+ gas on-chain). Additionally, a UserOperation specifies a gas limit for the validateUserOp step, and mempool nodes and bundlers will reject it unless this gas limit is very small (eg. under 200000). These restrictions replicate the key properties of existing Ethereum transactions that keep the mempool safe from DoS attacks. Bundlers and mempool nodes can use logic similar to today’s Ethereum transaction handling logic to determine whether or not to include or forward a UserOperation.

Maintained properties:

UserOperation that passes simulation checks is guaranteed to be includable until the sender has another state change, which would require the attacker to pay 7500+ gas per sender)UserOperation creates it automaticallyUserOperation with a significantly higher premium than the old one to replace the operation or get it included fasterNew benefits:

validateUserOp function can add arbitrary signature and nonce verification logic (new signature schemes, multisig…)Weaknesses:

Sponsored transactions have a number of key use cases. The most commonly cited desired use cases are:

This proposal can support this functionality through a built-in paymaster mechanism. A UserOperation can set another address as its paymaster. If the paymaster is set (ie. nonzero), during the verification step the entry point also calls the paymaster to verify that the paymaster is willing to pay for the UserOperation. If it is, then fees are taken out of the paymaster’s ETH staked inside the entry point (with a withdrawal delay for security) instead of the wallet. During the execution step, the wallet is called with the calldata in the UserOperation as normal, but after that the paymaster is called with postOp.

Example workflows for the above two use cases are:

paymasterData contains a signature from the sponsor, verifying that the sponsor is willing to pay for the UserOperation. If the signature is valid, the paymaster accepts and the fees for the UserOperation get paid out of the sponsor’s stake.sender wallet has enough ERC20 balance available to pay for the UserOperation. If it does, the paymaster accepts and pays the ETH fees, and then claims the ERC20 tokens as compensation in the postOp (if the postOp fails because the UserOperation drained the ERC20 balance, the execution will revert and postOp will get called again, so the paymaster always gets paid). Note that for now, this can only be done if the ERC20 is a wrapper token managed by the paymaster itself.Note particularly that in the second case, the paymaster can be purely passive, perhaps with the exception of occasional rebalancing and parameter re-setting. This is a drastic improvement over existing sponsorship attempts, that required the paymaster to be always online to actively wrap individual transactions.

ERC 4337 can be found here. There is an implementation in progress here. An early developer alpha version is expected to be coming soon, after which point the next step will be to nail down final details and conduct audits to confirm the scheme’s safety.

Developers should be able to start experimenting with account abstracted wallets soon!

Source: Medium